The title of this blog article shows obvious influence from that of my last two blog posts, ““Nairobi to Shenzhen”, and on to Guangzhou”, dated November 22 and December 15, 2009, which had its inspiration from the story of the book, “Nairobi to Shenzhen: A Novel of Love in the East”, about a young man of African heritage originally from Nairobi, Kenya, establishing a very different kind of family life and career in Shenzhen, a fast-growing metropolis in southern China across from Hong Kong.

Mark Ndesandjo’s life has been that of international, cultural and social mobility. I added the name Guangzhou to the title of my two blog posts to wish him greater success, after he had chosen to unveil his book to the international media in the city a short distance north that happens to be the economic center of southern China and a center of international trade from its historical days when it was known as the port of Canton to its modern status as the host of Canton Fair – one of the largest trade fairs in the world from where trade with Africa has been booming lately.

But Mark Ndesandjo’s life has also been a story of retreat. Born to parents educated in America, Mark received international education during his childhood in Nairobi, was sent to attend several elite universities in the United States, including Brown, Stanford, and Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia, and then embarked on an ambitious marketing career in the telecommunication industry. His life direction took a dramatic turn when he moved to China in 2002, but only after an unexpected layoff by the Canadian telecommunication giant at the time, Nortel Networks, shortly after 9/11, 2001.

Not to mention that Mark Ndesandjo is a half-brother of today’s U.S. President Barack Obama.

As interesting and intriguing as the Ndesandjo story was, and as was some of Obama’s politics and history which served as the backdrop for me to explore certain political issues of international interest, in this article I delve into a different type of cultural and social exchanges, one that had been practiced for many centuries in history, proliferated worldwide during the 19th century and become part of the international establishment by the dawn of the 20th century, but that ultimately went into retreat – the proselytizing of Christianity and its cultural and social dimensions.

From a personal perspective my focus will be on the arrival and evolution of Christianity in China, with special attention to certain stories about Protestant missionaries from Britain and America.

In this context, my choice of the title for this blog article has been influenced by Pace University historian Joseph Tse-Hei Lee’s article, “The Chinese Christian Transnational Networks Of Bangkok-Hong Kong-Chaozhou in the 19th Century” (2004, and a preceding 2001 article, “The Overseas Chinese Networks and Early Baptist Missionary Movement Across The South China Sea”), which reviewed the historical growth of Protestant Christian missions in southern China through influences from Christian missionary work among Chinese living in Siam (Thailand) and in Hong Kong. Dr. Lee is one of the first to paraphrase this part of Christian mission history in the notion of “Transnational Networks”, while some scholars have begun to emphasize the influences on America, Europe, the Muslim world, Asia and Africa by economic migrations and cultural interactions across multinational regions. (See, e.g., “A History of Maritime Asia and East Asian Regional Dynamism 1600-1900 – Maritime Asia from the Ryukyu-Okinawa to the Hong Kong Networks”, by Takeshi Hamashita, International Congress of Historical Sciences, August 2000; The Muslim World after 9/11, by Angel Rabasa, Rand Corporation, 2004; Religion Across Borders: Transnational Immigrant Networks, edited by Helen Rose Ebaugh and Janet Saltzman Chafetz, Altamira Press, 2002; “Africa: New Book Examines Yoruba Religion in Nigeria and the Diaspora”, by Vicki L. Brennan, allAfrica.com, June 8, 2005; Christian Democracy and the Origins of European Union, by Wolfram Kaiser, Cambridge University Press, 2007; “Transnational Networks, Domestic Democratic Activists and Defeat of Dictators: Slovakia, Croatia and Serbia, from 1998 to 2000”, Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, November 5, 2008; and, “Is there an Eastern Way to Practice Human Rights? A Comparison of Christian and Buddhist Transnational Networks in China”, by Yun Wang, International Studies Association 50th Annual Convention, February 2009.)

Multinational, and presumably grassroots-oriented movements, that is.

Long before the Bangkok-Hong Kong-southern China route of the Protestant missions’ first inroad into China beginning in the 1830s, there had been a history of Christianity in China – dating back to as early as the 7th century when Nestorian missionaries came via the Middle East and then the 13th century around the time of Marco Polo when Franciscan missionaries came to a Mongolian-ruled China. (See, e.g., “History of Christianity in China”, The Ricci 21st Century Roundtable on the History of Christianity in China.)

|

| 781 A.D. Chinese Nestorian Stele discovered in 17th century (Nestorian.org) |

The Nestorian Stele erected in China in the year 781 A.D. during the Tang (唐) dynasty recorded imperial reception granted by the second Tang Emperor, the Taizong Emperor (太宗) Li Shimin (李世民), in the year 635 A.D. for the religion and three years later the building of a church in the capital of Xi’an (Xian) with imperial blessing.

In this document the Roman Empire was referred to as “大秦”, (the Great Ch’in, or Qin – name of the first unified imperial Chinese dynasty in history), and Nestorian Christianity was referred to as “景教”, sometimes translated as “the Brilliant Teaching” or “the Luminous Religion” – although in my view a more appropriate translation would be “Religion of Scenes” and together “大秦景教”would mean “Religion of the Great Ch’in Scenes” or “Teaching of Great Ch’in’s Scenes”. (See, e.g., “Nestorian Stele: 唐景教碑頌正詮--陽瑪諾註”, Jesus Taiwan; “Chinese Nestorian Documents from the Tang Dynasty”, Centre for Late Antique Religion & Culture, Cardiff University; “Description and Significance of the Nestorian Stele, “A Monument Commemorating the Propagation of the Da Qin Luminous Religion in the Middle Kingdom” (大秦景教流行中國碑)”, Assyrian International News Agency; and, “Nestorian Stele”, Wikipedia.)

The reference to Nestorian Christianity as a religion of the “Great Ch’in” could have some additional significances: the Taizong Emperor who granted it the first imperial reception in the 7th century had held the title of the Ch’in Prince (秦王) prior to his succession to the throne – following a power struggle in which he deposed his elder brother the Crown Prince – and the imperial reception came in the same year 635 A.D. when his father, the retired Gaozu Emperor (高祖) Li Yuan (李渊), died. (See, e,g., The Shaolin Monastery: History, Religion, and the Chinese Martial Arts, by Meir Shahar, University of Hawaii Press, 2008.)

Nonetheless at the end of each historical era in China the Chinese Christian community the foreign missionaries had founded, and its culture, simply disappeared from the society, typically as a result of bans imposed by the officialdom. Thus Christianity had to be reintroduced to China at another time later, and its earlier heritage rediscovered by a new generation of foreign missionaries and their Chinese disciples.

Religious or intellectual prohibition and persecution were common in Chinese history. Both Buddhism and Nestorian Christianity were targeted during the late Tang dynasty in the 9th century but the prohibition did not succeed in eliminating the former as it did the latter. (See, e.g., “The Legacy of Chinese Christianity and China's Identity Crisis”, by Carol Lee Hamrin, Christianity in China, Global China Center, March 19, 2006.)

Meanwhile, Islam which had arrived in China in the mid-7th century – not long after its birth and shortly after Nestorian Christianity’s arrival – flourished, although initially the first mosque sanctioned by the Tang-dynasty emperor was built in Canton in southern China rather than in the capital Xi’an in western China – by a maternal uncle of the Prophet Muhammad. (See, e.g., “Islam in China”, by Mohammed Khamouch, Muslim Heritage, March 31, 2006.)

The most notorious official act of anti-religion and anti-intellectualism in Chinese history had come with the first unified imperial Chinese dynasty, the short-lived Great Ch’in (Qin) dynasty (circa 221–207 B.C.), ordered by the founding emperor Qin Shi Huang (秦始皇) famous for the construction of the Great Wall and for the Terracotta Warriors unearthed from his tomb. To enforce imperial centralized standards, the emperor ordered burning of most books and in that process buried alive hundreds of Confucian scholars. (See, e.g., “July 11, 1975: Unearthing Qin Shi Huang’s Terra-Cotta Army”, by Tony Long, July 11, 2007, Wired; and, “Burning of books and burying of scholars”, Wikipedia.)

But then in the other ‘Great Ch’in” – as the Chinese referred to the Roman Empire – such episodes of forced conformity and intolerance had also occurred beyond the Crucifixion of Jesus. Forcing conversion to Christianity was a cause for the destruction of the Library of Alexandria in Egypt in the 4th century, where the conversion was ordered by the Roman emperor and the enforcement carried out by Bishop Theophilus of Alexandria; this happened only several decades after the conversion of the Roman Empire to Christianity by Emperor Constantine and the founding of the empire’s eastern, Christian capital, Constantinople – previously the Greek colony of Byzantium – in today’s Turkey. Bishop Theophilus’s nephew and successor, Bishop Cyril, later in the 5th century was responsible for the Roman Catholic Church’s declaration of Bishop Nestorius of Constantinople and the Nestorian Christianity, which had initially arisen from Syria, as heretic. (See, e.g., The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Volume 2, by Edward Gibbon, Harper & Brothers, 1845; Doctrine and Practice in the Early Church, by Stuart George Hall, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 1992; The Library of Alexandria, by Kelly Trumble and Robina MacIntyre Marshall, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2003; and, Constantine and the Christian Empire, by Charles Matson Odahl, Routledge, 2004.)

During the early historical period most of the foreign religions coming to China, including Buddhism, Zoroastrianism, Manichaeism, Nestorianism and Islam, did so moving along the famous Silk Road to reach China’s northwest – although Islam in Canton arrived via the ocean in the south. (See, e.g., “Nestorianism in Central Asia during the First Millennium: Archaeological Evidence”, by Maria Adelaide Lala Comneno, Journal of the Assyrian Academic Society, Volume 11, No. 1; and, “Religions of the Silk Road”, Silk Road Seattle, Walter Chapin Simpson Center for the Humanities, University of Washington.)

Many nomadic tribes or nations of various ethnicities dotted the regions along the Silk Road, and that included the Ch’in (Qin) ancestors who had once been a nomadic tribe in the region of Tianshui (天水) in today’s Gansu (province) corridor through which ran the Chinese section of the Silk Road, just west of Xi’an. (See, e.g., “Qin (state)”, Wikipedia; “Brief Introduction to Shaanxi – History”, Shaanxi Sub-Council, China Council for the Promotion of International Trade; and, “Welcome to The Silk Road – Gansu Province”, China National Tourist Office.)

Today’s history literatures sometimes list the Han (汉) dynasty (206 B.C. - 220 A.D.) that followed the short-lived Ch'in as when the Silk Road began in China based on official records of it as a route of diplomatic exchanges between China and countries to the west including the Roman Empire. But archaeological finds have given strong indications of mutual influences in ancient crafts, from potteries to bronze tools to iron making, between Central Asia and China dating further back for centuries and millenniums, including along the Silk Road regions in China. Some scholars believe iron had been introduced to China from Central Asia. (See, e.g., “Sino-Roman Relations”, Wikipedia; “Themes in Global History: Trade, Economy, and Empires – Lecture 9: China I: Early Origins”, by Jari Eloranta, Department of History, Appalachian State University; History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Volume 1: The Dawn of Civilization: Earliest Times to 700 B.C., by Ahmad Hasan Dani and Vadim Mikhaĭlovich Masson, Motilal Banarsidass Publishers, 1999; “The earliest use of iron in China”, by Don Wagner, Nordic Institute of Asian Studies, University of Copenhagen, 1999; War and State Formation in Ancient China and Early Modern Europe, by Victoria Tin-bor Hui, Cambridge University Press, 2005; and, 从考古看丝绸之路祁山道的形成”, by 苏海洋 and 雍际春, Sichuan Social Science Online, September 23, 2009.)

Moreover, of the seven Chinese states that existed during most of the Warring States Period (475-221 B.C.) prior to Ch’in’s annexation of the other six, Ch’in had grown from a state of modest size whose territory included the Chinese section of the Silk Road at the time to occupying the entire western China, even though China’s technological innovation centers at the time – from silk textiles to bronze and iron weaponries – were in the Yangtze-River region state of Chu (楚) according to both historical literatures and archaeological discoveries. (See, e.g., Don Wagner, referred to earlier; Defining Chu: image and reality in ancient China, by Constance A. Cook and John S. Major, University of Hawaii Press, 2004; Victoria Tin-bor Hui, referred to earlier; “楚国丝绸——我国古代工艺水平最高的丝织品”, by 朱振汉, 荆州市档案信息网 (www.jzda.gov.cn); and, “战国时期的武器装备”, 中国国学网 (confucianism.com.cn), July 9, 2009.)

When Nestorian priest Alopen (阿罗本, or Aluoben) came in the 7th century and was received by the Tang Taizong Emperor, the Chinese referred to the religion as “the Iranian religion”; only until the mid-8th century not long before the Nestorian Stele’s erection in 781 A.D. that the name was changed to refer to the “Great Ch’in”. (See, e.g., Religions of the Silk Road: Overland Trade and Cultural Exchange from Antiquity to the Fifteenth Century, by Richard Foltz, Palgrave Macmillan, 2000; and, “Alopen”, Wikipedia.)

The Chinese name change for Nestorian Christianity thus coincided with the start of the Tang dynasty’s decline following a 7-year civil war in the mid-8th century when two military generals, An Lushan (安禄山, or Aluoshan) and Shi Siming (史思明), with ethnic origins from nomad tribes in Central Asia and the former an adopted son of the Tang emperor, launched a coup from their bases in today’s Beijing region in northern China, sacked capital Xi’an and named themselves the Yan (燕, Swallow) dynasty. It was the worst instance of treachery and destruction associated with the nomads to that point in recorded Chinese history. (See, e.g., “An Lushan” and “An Shi Rebellion”, Wikipedia; and, “China’s Cosmopolitan Empire – by Mark Lewis”, by Stephen Maire, United Press International.)

490 years after the Nestorian Stele. the Mongolians conquered China, founding the Yuan (元) dynasty in Beijing in A.D. 1271. That brought a comeback of the Nestorians – and also the arrival of Franciscan missionaries sent by the Pope in Rome. But in another century or so the Yuan dynasty was overthrown and the Mongolians driven out, and with them the Christians. (See, e.g., “Beijing – A guide to China’s Capital City: Beijing’s History”, China Internet Information Center; and, A World History of Christianity, by Adrian Hastings, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2000; and, “Yuan Dynasty”, Wikipedia.)

The 8th-century Nestorian Stele was rediscovered in the 17th-century after the Jesuit missionaries came to China and were officially received in the imperial court of the Ming (明) dynasty which had replaced the Mongolian Yuan two centuries earlier.

This time and onward, Christianity came primarily via the ocean route in the south rather than overland from the west or the north.

The Ming-dynasty era in Chinese history began with a southern focus not seen before in any other unified Chinese dynasty, partly due to such a preference by its founder Zhu Yuanzhang (朱元璋), the Hongwu Emperor (洪武). As a general in the White Lotus Rebellion in the Yellow-River region in northern China, Zhu Yuanzhang had moved south and taken the Yangtze-River city of Nanjing – at the time called Yingtian (应天) – as his base in the year 1356; and when he eventually defeated the other contenders, drove the Mongolians out of Beijing (Peking, 北京, “Northern Capital”) and back to Mongolia, and founded the Ming dynasty in 1368 A.D. he made Nanjing (Nanking, 南京, "Southern Capital") the national capital. (See, e.g., East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History, by Patricia Ebrey, Anne Walthall and James Palais, Cengage Learning, 2008; “Zhu Yuanzhang”, Impression of China, September 20, 2009; and, “Strength of Nanjing’s Bid for Hosting the Youth Olympics: A Long Historical & Cultural Link”, Nanjing Municipal People’s Government.)

One ancient legacy of the Nanjing region that is often overlooked as it had not occurred in Nanjing city itself, had had to do with Xiang Yu (项羽), a crucial leader of the rebellions against the short-lived Ch’in dynasty after Ch’in’s founder Qin Si Huang’s death in 210 B.C. Xiang Yu was instrumental in defeating the Ch’in army in 207 B.C. and deciding Ch’in’s final fate, and he later committed suicide at the north bank of Yangtze River about 35 miles outside today’s Nanjing city, while being pursued by the forces of Liu Bang (刘邦), soon-to-be founder of the Han dynasty. Xiang Yu, Liu Bang and later Ming-dynasty founder Zhu Yuanzhang were all from regions in the former Yangtze-River Chu (楚) State of the Warring States Period before Ch’in’s unification of China, but all from some distances north of today’s Nanjing. (See, e.g., “Xiang Yu”, “Emperor Gaozu of Han” and “Hongwu Emperor”, Wikipedia; “Suqian”, Jiangsu.NET; and, “Joyous Selected Trip to the North Bank of Yangtze River──The Direct Bus of North Bank Outing Started Running from April 5th!Nanjing Outing──Pukou”, Pukou Nanjing City (www.pukou.gov.cn).)

This southern focus of the Ming dynasty lasted from 1356 to only the end of the 14th century. One year after Zhu Yuanzhang’s death, from 1399 to 1402 his grandson and successor Zhu Yunwen (朱允炆), the Jianwen Emperor (建文), tried to establish a more civil regime but was militarily challenged and usurped by his uncle Zhu Di (朱棣), then the Yan Prince (燕王), whose dominion was based in the former Yuan-dynasty capital of Beijing. (See, e.g., “Jianwen Emperor”, Wikipedia; and, Perpetual Happiness: The Ming Emperor Yongle, by Shih-Shan Henry Tsai, University of Washington Press, 2002.)

If the name Yan appears similar to that of the Yan dynasty earlier – an 8th-century imperial-throne pretender proclaimed by the nomad rebellion of An Lushan and Shi Siming just before renaming of Nestorian Christianity as the “Religion of the Great Ch’in Scenes” in Tang Dynasty – that is because the northern region of China around Beijing was once the traditional territory of the Yan (Yen, 燕, Swallow) State prior to Ch’in’s unification of China. (See, e.g., “Yenching University”, Wikipedia.)

The victorious Yan Prince Zhu Di who became the Yongle Emperor (永乐), viewed himself as the second founder of the Ming dynasty and decided to move the national capital back north to Beijing, going against the trend of economic and population growths in the Yangtze-River region and declines in the northern region, which was making the south far more prosperous. The official move took place in October 1420 after a brand-new capital – today’s Beijing city – was constructed not far from the old Yuan-capital site. (See, e.g., The Cambridge history of China, Volume 7: The Ming dynasty, 1368-1644, Part 1, by Frederick W. Mote, Denis Crispin Twitchett and John King Fairbank, Cambridge University Press, 1988; Imperial China 900-1800, by Frederick W. Mote, Harvard University Press, 2003; and, Chinese Spatial Strategies: Imperial Beijing, 1420-1911, Jianfei Zhu, Routledge, 2004.)

|

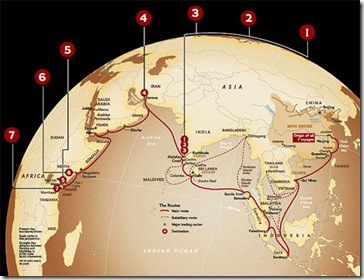

| Map of Zheng He’s seven voyages, 1405-1433 A.D. (“China’s Great Armada”, National Geographic, July 2005) |

But even with the move back to Beijing the Ming dynasty still had another southern focus during the first half of the 15th century, that of sending large naval expeditions to visit countries in Southeast, South and West Asia and in East Africa – something never done before by a Chinese dynasty. From 1405 to 1433 A.D., a total of seven official envoys, each consisting of tens or hundreds of large ships, with crews totalling tens of thousands including sailors and soldiers, sailed under the command of Admiral Zheng He (郑和).

From a family that had been Muslim for generations whose family name was Ma (马, Horse), a name common among Chinese Muslims, Zheng He’s heritage can be traced to a Central Asian Muslim nobleman and the Prophet Muhammad’s descendant, who joined the Mongolians under Genghis Khan (成吉思汗), later served as the governor of the Yuan-dynasty capital of Beijing (Yenching, 燕京) and was given a dominion in the southwestern province of Yunnan. When the Mongolian Yuan dynasty was overthrown, Zheng He became a child captive of the Ming forces in Yunnan, was made a eunuch, and later became a protege of the Yongle Emperor. Zheng He’s voyages reached countries no less than Indonesia, Sri Lanka, Yemen and Somalia, and on his last voyage he made pilgrimage to the holiest city of Islam, Mecca in Saudi Arabia, before passing away during the return sail to China. (See, e.g., “The Admiral Zheng He”, by Paul Lunde, Saudi Aramco World, Vol. 56, No. 4, 2005; “Zheng He (1371-1433), the Chinese Muslim Admiral”, Islam for Today; “Ancient Chinese Explorers, Part 2: Exploits of the eunuch admiral Zheng He”, NOVA Online, PBS; “朱棣缘何派郑和下西洋”, by 陆元, 档案大观; and, “Zheng He” and “赛典赤·赡思丁”, Wikipedia.)

Nanjing during this time enjoyed a boom of its big shipyards building many of the ships for Zheng He’s voyages. (See, e.g., “Zheng He’s Voyages of Discovery”, by Richard Gunde, UCLA International Institute, April 20, 2004; and, “China showcases nautical hero Zheng He's shipyard in Nanjing”, China Daily, November 7, 2005.)

There were persistent rumours that one of the objectives of these Ming naval expeditions was to hunt for Yongle Emperor’s nephew, the previous Ming emperor, who when usurped by the uncle in 1402 might not have died but escaped elsewhere, possibly overseas. (See, e.g., Frederick W. Mote, referred to earlier; “Ming Emperor overseas?”, Chinatownology; and, “Yongle (emperor of Ming dynasty): Foreign policy”, Encyclopaedia Britannia.)

The rumours may not have been completely unfounded, considering that later when Ming was conquered by the Manchurian Qing dynasty in the 17th century the last claimant of the Ming imperial throne, the Yongli Emperor of South Ming, who by then had converted to Christianity and sought the support of Rome through Jesuit missionaries in China, fled to Burma before a Chinese military invasion captured and executed him. (See, e.g., Asian Borderlands: The Transformation of Qing China's Yunnan Frontier, by Charles Patterson Giersch, Harvard University Press, 2006; and, “Medicine and Culture: Chinese-Western Medical Exchange (1644-ca.1950)”, Pacific Rim Report, University of San Francisco Center for the Pacific Rim.)

The military expedition to capture the last South Ming emperor was launched from Yunnan province and led by Wu Sangui (吴三桂), a former Ming military general who had played the crucial role of opening the gate of the Great Wall to let the Manchurians in to attack Beijing, been rewarded with a princely title for that and put in charge of Yunnan– not unlike Zheng He’s forefather with the Mongolians though in a much bigger role. (See, e.g., Frederick W. Mote, referred to earlier.)

Legends never die. In 1999 before the New Millennium, Nicholas D. Kristof of The New York Times wrote a long article about visiting some of the places of significance in the history of Zheng He’s voyages, and trying to discover, on the island of Pate at the Kenyan coast, descendants of rumoured survivors of a Chinese shipwreck from long ago – feeling intrigued by similarities between some local customs and traditional Chinese customs. (See, “1492: The Prequel”, by Nicholas D. Kristof, The New York Times, June 6, 1999.)

After Zheng He’s death the Ming-dynasty government ended further naval expeditions and, rather inexplicably, by around the year 1479 official records of Zheng He’s voyages were destroyed and building of large ships was banned. (See, e.g., China: A New History, by John King Fairbank and Merle Goldman, Harvard University Press, 2006.)

Perhaps other matters called for preoccupation and for caution against the southern focus, matters such as continuing warfare in the far north against the Mongolians, and setback in the south where Vietnam won recognition of independence after a short period of Chinese occupation, or perhaps the objectives of the naval expeditions had been achieved: some of Zheng He’s crews stayed behind in places like Malacca in Malaysia and formed overseas Chinese communities there; the influences from his voyages were now enabling more Chinese to emigrate to these regions; and many of the countries the envoys visited established diplomatic relations with China and sent delegations to pay “tributes” for trade privileges with the largest country on earth – where the government preferred a Confucian hierarchical, authoritarian official-control approach to trade. (See, e.g., Frederick W. Mote, Denis Crispin Twitchett and John King Fairbank, referred to earlier; Admiral Zheng He & Southeast Asia, edited by Leo Suryadinata of International Zheng He Society, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore, 2005; John King Fairbank and Merle Goldman, referred to earlier; and, “Museum tells past stories of overseas Chinese”, Global Times, November 18, 2009.)

John King Fairbank (费正清) and Merle Goldman, prominent scholars in Chinese history, even go as far as asserting that “Ming China almost purposely missed the boat of modern technological and economic development” (see, John King Fairbank and Merle Goldman, referred to earlier).

The decline of maritime power led to serious deterioration of piracy problems from the early 16th century on, with a mixture of Chinese and Japanese pirates plaguing the eastern and southern Chinese coasts, from which the Ming government had to retreat further as it no longer had a strong navy. (See, e.g., “Piracy in early modern China”, by Robert Antony, International Institute for Asian Studies Newsletter, The Netherlands, March 2005; and, “Wokou”, Wikipedia.)

Meanwhile, other important events were happening in what China considered the West.

20 years after Zheng He’s seventh and last voyage during which he is thought to have made a Mecca pilgrimage fulfilling a Muslim’s wish in life, in 1453 A.D. the Muslim Ottoman Empire conquered Constantinople, center of Eastern Christianity originating from which Nestorianism had officially reached China in the 7th century. (See, e.g., History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey, Volume 1, by Stanford J. Shaw, Cambridge University Press, 1976.)

In 1479-80 when Chinese official records of Zheng He’s voyages were destroyed, Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand ascended to the Spanish throne after a war of succession, and began the Spanish Inquisition to purify the Catholic churches in Spain, rooting out Jews, Muslims and heretics. (See, e.g., “Spanish Inquisition” and “Catholic Monarchs”, Wikipedia.)

Then in 1486 A.D., 130 years after the Ming-dynasty founder Zhu Yuanzhang’s conquer of Nanjing, Christopher Columbus, an Italian maritime explorer in Portugal, was granted an audience with Queen Isabella of Spain on his proposals to sail to China and India by circumnavigating the world from the Atlantic in the hope of establishing a new route to compensate for the loss of land routes due to the advance of the Muslim conquers. (See, e.g., Discovering Christopher Columbus: How History Is Invented, by Kathy Pelta, Twenty-First Century Books, 1991; “Christopher Columbus: Biography”, The Order Sons of Italy in America; and, “Christopher Columbus”, Wikipedia.)

Columbus reached and ‘discovered’ America in 1492.

Some scholars have since argued that Christopher Columbus’s true identity had been that of a young Greek prince in the Byzantine Empire who had fled when the Byzantine capital Constantinople fell to the Muslims in 1453, and who identified himself as from Genoa, Italy for the reason that his true birth place had been the Greek island Chios, under Genoese rule at the time. (See, e.g., “Christophoros Columbus: A Byzantine Prince from Chios, Greece”, by Ruth G. Durlacher-Wolper, Australian Macedonian Advisory Council, American Chronicle, November 27, 2008.)

But there is also the contention, by former British naval officer and author Gavin Menzies, that part of Zheng He’s fleets during his sixth voyage, 1421-1422 (or 1423), actually went in the direction of and reached America. (See, 1421 The Year China Discovered America, by Gavin Menzies, HarperCollins Publishers, 2003.)

In any case, history as written and known today is that Christopher Columbus’s discovery marked the start of a new world era with the Portuguese in the role of global maritime traders and the Spanish as international colonizers. (See, e.g., The Emergence of the Global Political Economy, by William R. Thompson, Routledge, 1999.)

By 1509-1511 overseas Chinese traders hooked up with the Portuguese who took Malacca under their control, and by 1513-16 Portuguese ships from Malacca were in Canton to trade, one of them led by Rafael Perestrello, a cousin of Christopher Columbus’s wife. (See, e.g., The Cambridge history of China, Volume 8: The Ming Dynasty, 1368-1644, Part 2, by Denis Crispin Twitchett and John King Fairbank, Cambridge University Press, 1978; World Civilization: A Brief History, by Robin W. Winks, Rowman & Littlefield, 1993; and, “Rafael Perestrello”, Wikipedia.)

During the 16th century the commercial island of Macao off the southern Chinese coast near Canton was allowed de facto Portuguese control by the Ming government. (See, e.g., Denis Crispin Twitchett and John King Fairbank, referred to earlier; and, “Historic Centre of Macao”, UNESCO World Heritage.)

The Portuguese were setting up trade posts not only from Europe to Asia, but also from Africa to Europe and later to America where black salve trade was involved; they had built a permanent trade post in the Gold Coast of West Africa, i.e., today’s Ghana, during the 15th century – a subject related to the topics of my last two blog posts, ““Nairobi to Shenzhen”, and on to Guangzhou”. (See, e.g., Four Centuries of Portuguese Expansion, 1415-1825: A Succinct Survey, by C. R. Boxer, University of California Press, 1972; and, The Atlantic Slave Trade: New Approaches to the Americas, by Herbert S. Klein, Cambridge University Press, 1999.)

Catholic missionaries, most notably Jesuit priests (members of the Society of Jesus), began to arrive in China in the late 16th century via Macao, and establish missions in Kwangtung (Guangdong) province. The Jesuits who came to China were of diverse European national backgrounds, ranging from Italian to Belgian, German to Polish, and the Jesuit influences, with their emphasis on the Western knowledge of mathematics, science and astronomy, would grow to reach Beijing and other regions of China. (See, e.g., “Jesuit China missions”, Wikipedia.)

The first Jesuit missionaries to China were Father Michele Ruggieri (罗明坚, Luo Ming-jian) who arrived at Macao in 1579, and Father Matteo Ricci (利玛窦, Li Ma-dou) a few years after. The two founded missions in Kwangtung during the late 16th century, before Ricci went on to Beijing.

Before reaching Beijing, Ricci wrote a treatise to explain the “Memory Palace” to the sons of the governor of Jiangxi province (Guangdong’s neighbour to the northeast), about an old intellectual method of memorizing through identifying objects and subjects to remember with various parts of a palace or various structures of different sizes, styles and functionalities. Ricci pointed out to the Chinese that these palaces were not necessarily meant to be in the real world. (See, e.g., “Engines of Our Ingenuity, No. 1226: Ricci’s Memory Palace”, by John H. Lienhard, University of Houston, 1997; and, “Building the Palace”, by Douglas Anderson, Ricci Street – an online MBA community, Medaille College, Buffalo, NY, March 20, 2000.)

|

| World Map by Matteo Ricci, 1602 A.D. (Henry Davis Consulting) |

In the imperial court in Beijing, Ricci produced world maps – the first Chinese maps to utilize Western knowledge of the world – on which he placed China near the center of the view. That caused quite a bit of controversy back in Europe. (See also, e.g., “Cartography and Memory”, by Alexander Fabry, The Harvard Advocate, Winter 2009; and, “China: Hong Kong: Matteo Ricci maps did not put China at centre of the world”, January 26, 2010, Spero News.).

Among other Jesuits who came to China during the 17th century was Father Johann Schreck (邓玉函, Deng Yu-han), a noted astronomer, physicist, friend of Galileo and Kepler, and the 7th elected member of the Lincean Academy – Galileo being its sixth member; Schreck brought the telescope to China. (See, e.g., Science and Civilisation in China, Volume 3: Mathematics and the Sciences of the Heavens and the Earth, , by Joseph Needham, Cambridge University Press, 1959; and, “Accademia dei Lincei”, Wikipedia.)

|

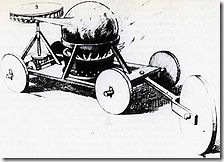

| World's first car designed by Ferdinand Verbiest in China, 1672 A.D. (Wikipedia) |

Other noted Jesuit innovators in China included Father Ferdinand Verbiest (南怀仁, Nan Huai-ren), who is now credited with designing and building the world’s first (model) automobile, in the year 1672 in China. (See, e.g., “The Mechanics of Heaven: Jesuit Astronomers at the Qing Court”, by Mark Stephen Mir, The Ricci Institute for Chinese-Western Cultural History, University of San Francisco, August 14, 2004; “The Jesuits and Sino-Western Technology”, by Mark Mir, The Ricci Institute for Chinese-Western Cultural History, University of San Francisco; and, “Ferdinand Verbiest”, Wikipedia.)

From the time of Schreck to the time of Verbiest China changed, through great upheavals: the same year 1630 when Schreck died a peasants’ rebellion began, led by Li Zicheng (李自成) of Yan’an (Yanan, later the center of the Chinese Communists led by Mao Zedong during World War II), which eventually overthrew the Ming dynasty but was then overcome by the Manchurians from the northeast who established the Ch’ing (清, Qing) dynasty, in 1644. (See, e.g., “Li Zicheng” and “Qing Dynasty”, Wikipedia.)

Geographically, it was not a long distance for the Manchurians to come south to take Beijing and claim it as their capital, after Wu Sangui opened the gate of the Great Wall to them. After all, the first Chinese regime making Beijing the capital had been their ancestral Jin (金, Jurchen) dynasty in the 12th and 13th century, which had conquered northern China and forced the Song (宋, Sung) dynasty to retreat south and become South Song – prior to conquers of both by the Mongolian Yuan. (See, e.g., The Cambridge History of China, Volume 6: Alien Regimes and Border States, 907-1368, by Denis Twitchett and Herbert Franke, Cambridge University Press, 1994.)

Like last time, resistances to the Manchurian rule from forces loyal to the Ming dynasty retreated to southern China under the banner of South Ming dynasty, and they were not put down until the early 1660s.

By this time, the Jesuit missionaries had converted about 100,000 Chinese to Christianity, with the highest concentrations in Beijing, in the Shaanxi region where the old capital of Xi’an is located, and in southern China. The last emperor of South Ming, the Yongli Emperor (永历), or at least his family, was among newest Chinese converts, and after retreating to Nanjing, then Canton, and then Guangxi province in the southwest, he sent Jesuit missionary Father Michał Boym (卜弥格) to lobby Portugal, France and Rome for support to counter Qing military offensives and re-establish the Ming dynasty; but by the time Boym returned to China in 1659 Yongli was near complete defeat and soon to flee into Burma, and Boym died on the way to reach the South Ming emperor – sick and exhausted. (See, e.g., “Southern Ming Dynasty”, “Zhu Youlang, Prince of Gui” and “Michał Boym”, Wikipedia; “卜弥格 (Michel Boym, 波兰, 1612—1659)”, National Library of China; “Medicine and Culture: Chinese-Western Medical Exchange (1644-ca.1950)”, Pacific Rim Report, University of San Francisco Center for the Pacific Rim; and, Journey to the East: the Jesuit Mission to China, 1579-1724, by Liam Matthew Brockey, Harvard University Press, 2007.)

During this time, in 1658 the Jesuit society in Rome redrew its map and transferred its jurisdiction of the southern China regions of Guangdong, Guangxi and Hainan island from the “Vice-Province” of China to the “Province” of Japan, boosting the status of Macao as an international Jesuit missionary center. (See, e.g., Liam Matthew Brockey, referred to earlier.)

During the 1660s some of the Jesuit missionaries in Beijing suffered severe prosecutions by the Qing government: Ferdinand Verbiest first arrived in Beijing only to find jail, with Father Johann Adam Schall von Bell (湯若望, Tang Ruo-wang), the chief astronomer of the imperial court, already in prison in the so-called “Calendar Case” (历狱), accused of “falsifying the calendar, promoting a heterodox sect, and preparing an invasion by Europeans”. Schall von Bell was given the death penalty but it was later commuted, and he died after several years of prison life. Several of his Chinese assistants were executed, and most of the Jesuit missionaries in Beijing were exiled to Canton – with Verbiest one of the few exceptions during this period of “Canton exile”. (See, e.g., “Jesuit Astronomers in Beijing, 1601-1805”, by Agustin Udias, Quarterly Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society, December 1994; Mark Stephen Mir, referred to earlier; The Interweaving of Rituals: Funerals in the Cultural Exchange between China and Europe, by N. Standaert, University of Washington Press, 2008; and, “历狱”, Wikipedia.)

At the time there had indeed been European invasions, but not the kind of Portuguese administration of Macao for trade purposes agreed to by the Ming government, or possible promises of military assistance to the South Ming dynasty from some European countries, which came too late anyways.

It was the occupation and attempted colonization of the island of Taiwan (Formosa) off the southeast coast, by the Netherlands (the Dutch East India Company) and Spain beginning in the 1620s, at a time when the Manchurians in the northeast were also in their early stage of proclaiming hostility and insurrection against the Ming government. (See, e.g., The Search for Modern China, by Jonathan D. Spence, W. W. Norton & Company, 1991; How Taiwan Became Chinese: Dutch, Spanish, and Han Colonization in the Seventeenth Century, by Tonio Andrade, Columbia University Press, 2008; “History”, Portal of Republic of China (Taiwan) Diplomatic Missions; and, “How Taiwan became Chinese: Dutch, Spanish, and Han Colonization in the Seventeenth Century”, by Anne Gerritsen, Reviews in History, March 2010.)

By the 1660s when the victorious Qing dynasty began to prosecute the “Calendar Case” in the imperial court in Beijing, the colonial rules in Taiwan was actually ending after Chinese pro-Ming forces – under the command of the legendary Zheng Chenggong (郑成功, also known as Koxinga) from the family of a pirate-kingpin father and a Japanese mother – in 1662 captured Taiwan as their base of anti-Qing operations. Prior to that, in 1659 they had laid an offensive siege to Nanjing unsuccessfully. (See, e.g., Jonathan D. Spence, referred to earlier; and “Koxinga”, Wikipedia.)

As a matter of fact it was the Qing government that then cooperated with the Dutch to try to conquer Taiwan, but Qing’s attempts did not succeed until the battle of Penghu (Pescadores) in 1683.

Over a century after Matteo Ricci’s arrival in Beijing, in the early 18th century Father Giuseppe Castiglione (郎世宁, Lang Shi-ning) arrived at the imperial court of Qing. Born in the year 1688 in which Ferdinand Verbiest died, Castiglione was an accomplished artist when he went to China. Infusing his knowledge of Western arts and architecture with the Chinese arts and architecture, Castiglione became an imperial-palace painter, depicting several generations of emperors, their palaces and their lives in grandeur. (See, e.g., “New Visions at the Ch’ing Court – Giuseppe Castiglione and Western-Style Trends”, National Palace Museum, Taipei.)

Castiglione also helped design the Yuan-Ming Palace (圆明园) – finally an ambitious imperial palace with rich architectural styles from both the East and the West! (See, e.g., “18th Century Chinese Garden Architecture”, BibliOdyssey (blog), April 28, 2006; “Giuseppe Castiglione and Court Art in Qianlong’s Reign of Qing Dynasty”, Century Online Chinese Art Networks; and, “Old Summer Palace”, Wikipedia.)

The name of the Yuan-Ming Palace, 圆明园, is sometimes translated as the “Garden of Perfect Splendour” or the “Garden of Perfect Brightness”. (See, e.g., “Yuanming Yuan, The Garden of Perfect Brightness”, China Heritage Quarterly, China Heritage Project, The Australian National University, December 2004; and, “Yuanmingyuan (Garden of Perfect Splendor)”, Yuanmingyuan Park.)

But my preferred translation for the name 圆明园 would be the “Perfect Ming Garden” or the “Perfectly Round Ming Garden”, for the reasons that the Chinese word “圆”can mean ‘perfect’ or ‘round’ and the word “明”which means ‘bright’ is also the name of the Ming dynasty preceding Qing (清, Ch’ing).

Others may dismiss my interpretation offhand simply because of official Qing taboos on things related to the previous Ming dynasty, taboos that needed to be taken seriously such as in the infamous “Case of Ming Dynasty History” (明史案) in the 1660s – thus use of the same word “明”in naming the new imperial palace could not possibly refer to the Ming dynasty. (See, e.g., Autocratic Tradition and Chinese Politics, by Zhengyuan Fu, Cambridge University Press, 1993; and, “元明清史”, by 王天有 and 成崇德, 五南圖書出版股份有限公司, 2002.)

My argument for the merits of my interpretations is based on reading of the Yongzheng (雍正) Emperor’s essay, “圆明园记”(“Yuan-Ming Garden Notes”): Yongzheng states in his very first use of the word “明”outside of the Garden’s name, that the land had originally been expropriated by his father (the Kangxi Emperor, 康熙) from a site of dilapidated old mansions of former Ming-dynasty families – through reducing the size of their lots – for the construction of the spring garden Chang-Chun Yuan (畅春园, one of the gardens that formed the Yuan-Ming Palace) – “就明戚废墅,节缩其址,筑畅春园”; Yongzheng then states that he asked for a garden also and was granted a section of the land; later in the essay, to explain the meanings of the Yuan-Ming name granted by his father, Yongzheng composes the phrases “圆而入神”, meaning “round as to enter ecstasy”, and “明而普照,达人之睿智”, meaning “bright as to universally illuminate, reaching man’s wisdom”. (See, “圆明园记”, by 雍正, Yuan-Ming Palace (www.yuanmingyuan.cn); or, “圆明园记”, Yuanmingyuan Park.)

In other words, in his essay on the Yuan-Ming Palace the Ch’ing emperor did not try to avoid the use of the word “明”as a reference to the Ming dynasty, on the contrary used it specifically referring to the origin of the palace site, and in doing so in effect made a contrast between the high ideal he saw as embedded in the “brightness” meaning of the word “明”to that of the dilapidated state of the former-“Ming” mansions.

Thus in my view the Ch’ing emperor had an aspiration for “perfection” and “illumination” not only in the physical senses but in the social and intellectual senses, and quite possibly viewed it as an imperial dream the previous Ming-dynasty circles – if they had harboured it – had failed to achieve.

Such goals of “perfection” and “illumination” may indeed have been quite remote in Chinese history to that point, or at least to the point when the Ch’ing dynasty first arrived, despite the impressive accomplishments of the Chinese civilization.

When the Nestorian Stele was erected in the 8th century to record 7th-century imperial reception given to Nestorian Christianity by the Tang-dynasty Taizong Emperor – roughly one millennium before the Yuan-Ming Palace’s construction – the name “大秦景教”was used; I have expressed my view earlier that the meaning of the word “景”was more about the conveyance of the religion through presenting the “scenes” of the Western “Great Ch’in”, than about the religion being “brilliant teaching” or “luminous religion”.

An important point is that the cultural exchanges between China and the West at the time of Nestorian Christianity did not bring the advanced knowledge of the West to China, knowledge otherwise disseminated among the various Western cultures.

Take for instance mathematics – something of personal interest to me as a mathematician by training. The books of Elements, written by the Greek mathematician Euclid of Alexandria, Egypt, in the 3rd century B.C. on the fundamentals of mathematics, not only represented a crowning achievement of ancient mathematics but also a mathematical foundation for studying other scientific subjects such as the Ptolemy theory of astronomy about the universe rotating around a round, stationery earth. Euclid’s books were translated to Latin in the 5th or 6th century A.D., received by the Arabs around 750 A.D. and translated into Arabic around 800 A.D. – close to the time of the Nestorian Stele! Yet the first Chinese copy of Elements did not appear until 1607 – translated by none other than the pioneer Jesuit missionary Matteo Ricci and his Chinese collaborators – and it was only the first 6 books of the 15 volumes. The rest were not translated into Chinese until the 1850s – first published in 1859. (See, e.g., Mathematical Thought from Ancient to Modern Times, Volume 1, by Morris Kline, Oxford University Press, 1990; Euclid in China: The Genesis of the First Chinese Translation of Euclid’s Elements in 1607 & Its Reception up to 1723, by Peter M. Engelfriet, Brill, 1998; Science and Religion, 400 B.C. to A.D. 1550: From Aristotle to Copernicus, by Edward Grant, JHU Press, 2006; “A Study of the Translation and Fate of the Elements in Different Civilizations”, by F. C. Chen, Journal of Chinese Studies, 2008; and, “Euclid’s Elements”, Wikipedia.)

As discussed, after some initial southern focuses – particularly Zheng He’s voyages in the first part of the 15th century – the Ming dynasty turned isolationist, and self-limiting rather than innovative; and by the early 17th century when Jesuit missionaries began to arrive and bring scientific and technological knowledge to China, European colonial powers, i.e., the Portuguese, the Dutch and the Spanish, were also at the door.

No wonder the Qing’s Yongzheng Emperor could think of the Ming circles as failures.

Even with the Jesuit missionaries’ natural bend toward the scientific disciplines, some important Western knowledge, in astronomy, anatomy and medicine in particular, was either not transmitted to or not accepted in China, during the Ming and Qing eras.

In astronomy, despite the presence of many Jesuit astronomers in the imperial Qing court, for over a century until 1760 the Jesuits misrepresented the Copernicus theory to the Chinese, not telling them it was about a sun-centered planetary system. They did so in accordance with a ban on teaching Galileo’s theory, issued by the Roman Catholic Church in 1616 and in force till 1757. (See, e.g., “Jesuit Astronomers in Beijing, 1601-1805”, by Agustin Udias, Quarterly Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society, December 1994; and, “Copernicus in China or, Good Intentions Gone Astray”, in Science in Ancient China: Researches and Reflections, by Nathan Sivin, Variorum, 1995.)

The Jesuit astronomers did so despite their closeness to the center of European astronomy: Johann Schreck had been a contemporary and friend of Galileo and Kepler, Johann von Bell had been a Roman College student learning Galileo’s new discoveries that substantiated a sun-centered planetary system, and when Michał Boym first went to China, at Kepler’s request he brought along the latter’s mathematical tables on the Copernicus theory. (See, e.g., Science and Civilisation in China, Volume 3: Mathematics and the Sciences of the Heavens and the Earth, , by Joseph Needham, Cambridge University Press, 1959; and, Between Copernicus and Galileo: Christoph Clavius and the collapse of Ptolemaic cosmology, by James M. Lattis, University of Chicago Press, 1994.)

In fact in the year 1610 when Galileo made his discoveries using a modernized telescope, Jesuit missionary Father Manuel Dias, Jr. (阳马诺) arrived in China, where in 1614-15 – the year before the Church’s ban on Galileo’s theory – he published a Chinese book, “天問略”(“Epitome of Astronomy”), on European astronomy and mentioned Galileo and the latter’s new discoveries. (See, e.g., Agustin Udias, referred to earlier; Chinese Books and Documents in the Jesuit Archives in Rome: Descriptive Catalogue: Japonica-Sinica I-IV, by Albert Chan, M.E. Sharpe, 2002; and, The Jesuits, the Padroado and East Asian science (1552-1773), by Luis Saraiva and Catherine Jami, World Scientific, 2008.)

Dias became friends with celebrated Chinese scientist and scholar Xu Guangqi (徐光启) – a collaborator of Matteo Ricci’s in the translation of Euclid’s Elements – and served for many years as the leader of the Jesuits in China, and later in 1644 – the year the Ming dynasty was ended and Qing dynasty came – published an influential commentary on the 781 A.D. Nestorian Stele rediscovered after the Jesuits arrived in China. (See, e.g., “Nestorian Stele: 唐景教碑頌正詮--陽瑪諾註”, Jesus Taiwan; The Story of a Stele: China’s Nestorian Monument and Its Reception in the West, 1625-1916, by Michael Keevak, Hong Kong University Press, 2008; and, “陽瑪諾, 作者生平”, Hong Kong Catholic Diocesan Archives.)

The Chinese might have only gotten the “scenes” the first time around (i.e., with Nestorian Christianity), and they weren’t “illuminated” this time, either.

The orthodoxy by the Roman Catholic Church in controlling dissemination of scientific thought was unfortunate during an era when transformational scientific discoveries and progresses – especially Newton’s work on the mathematics and physics of motion – were taking place in Europe.

In anatomy and medicine, efforts by the Jesuits to convince the Kangxi Emperor (Yongzheng’s father) about the Western system of universal human anatomy – instituted since the ancient Greek time of Aristotle – met with great scepticism and indifference. For instance, in a published lecture to his sons, the Kangxi Emperor admonished the food and drink south of the Yangtze River, stating that the southern cuisine would make northerners soft and weak like the southerners, and that following of the southern trend must be avoided. The anatomical knowledge brought by the Jesuits was not disseminated outside the imperial court during that time. By as late as the 19th century noted Chinese scholar Yu Zhengxie (俞正燮) still wrote an essay to refute the Jesuits’ illustrations of the human body two centuries earlier, arguing that the Chinese human organs were of different structures from the Westerner’s, and that it explained the differences in religious beliefs. (See, e.g., “Medicine and Culture: Chinese-Western Medical Exchange (1644-ca.1950)”, Pacific Rim Report, University of San Francisco Center for the Pacific Rim; Fighting Famine in North China: State, Market, and Environmental Decline, 1690s-1990s, by Lillian M. Li, Stanford University Press, 2007; and, “西风东渐的轶闻趣事”, by 周真真, Jiefang Daily, December 5, 2008.)

Medicine is also something of personal interest as I have discussed in some of my earlier blog posts and in my Chinese blog post, “忆往昔,学历史智慧(一)——从幼年的故事说起”(“Reminiscing the past, learning history’s wisdom (Part 1) – starting from childhood stories”), that my maternal grandmother’s grandfather became one of the first doctors of Western medicine in Kwangtung’s Shantou (Swatow) region when in the 1860s the region’s first hospital, the Swatow Mission Hospital, was founded by Dr. William Gauld of the English Presbyterian Mission and my great-great grandfather was fortunate enough to study medicine there.

Such huge gulfs in contemporary knowledge and understanding between the West and China serve as a backdrop to my glimpse into the thoughts it might have taken for the Yongzheng Emperor (who reigned from the early 1720s to the mid-1730s) to articulate a dream of perfect, universal illumination as embodied in the name of the Yuan-Ming Palace.

Among Giuseppe Castiglione’ paintings for the Yuan-Ming Palace was a portrait of a Western palace lady – one of six portraits on the “separation wall” in the back-corridor of the Four-Convenience Hall, completed in the 4th year of Yongzheng’s reign, circa 1726 (coincidentally, Yongzheng himself was the fourth son of his father Kangxi). The portraits were adapted from Western portrait prints provided by court officials, with the horses in the prints omitted at the emperor’s order.

After viewing this portrait, the Yongzheng Emperor issued an edict: the appearance was painted well but the several steps behind were too high, too difficult to walk on, and their gradation too close; Castiglione should repaint with the background adjusted to the depth of the three rooms in the Hall, and leave this one for entertainment use in the backroom. (See, “圆明园四宜堂隔断贴画:西洋仕女”, by 苏金成, 中国美术研究 (Journal of Chinese Fine Arts), Number 3 (May-June) 2009).

Unfortunately, while Castiglione was working on artistic projects such as the portrait above and on designing expansions of the Yuan-Ming Palace, Western missionaries were beginning to be banned from proselytizing in China following escalations of a nearly century-old dispute between Beijing and Rome over whether to allow Chinese Christians to practice Confucian rites which included ancestor worship, i.e., if the rites were not idolatry.

From the start of the Jesuit missionary work in China in the early 17th century, there were strong oppositions from Dominican missionaries who were closely associated with Spanish rule in the Philippines, against the Jesuits’ eclectic positions on Confucian rites. Throughout the 17th century different popes in Rome took different positions on the issue. The Kangxi Emperor’s 1692 edict of tolerance toward Christianity and his approval, in the year 1700, of the Jesuit interpretation of the rites failed to change Rome’s hardening position on the issue: in 1715 Pope Clement XI published an apostolic constitution requiring all missionaries to take an oath abiding by directives against the Chinese rites. (See, e.g., “George Minamiki, S. J., The Chinese Rites Controversy from Its Beginnings to Modern Times (Chicago: Loyola University Press, 1985)”, by Paek-seop Shim, Journal of Religious Studies, Vol. 23, 2004; “Order of Preachers (OP) 聖多明我會”, The Ricci 21st Century Roundtable on the History of Christianity in China, and, and, “Chinese Rites controversy”, Wikipedia.)

In 1721 Kangxi issued a ban prohibiting foreign missionaries from preaching in China, specifically referring to it as a response to the Pope’s directives against Chinese Confucian rites.

Two years after taking over the throne upon winning a power struggle following his father’s death, in 1724 (i.e., two years before the Castiglione painting shown in this blog post) Yongzheng issued an edict banning Christianity in China altogether. The ban was enforced during the long reign of his son, the Qianlong Emperor (乾隆), which lasted to near the end of the 18th century. (See, e.g., God and Caesar in China: Policy Implications of Church-State Tensions, by Jason Kindopp and Carol Lee Hamrin, Brookings Institution Press, 2004; and, Journey to the East: the Jesuit Mission to China, 1579-1724, by Liam Matthew Brockey, Harvard University Press, 2007.)

By the time of the ban in 1724 there were several hundred thousand Chinese Christian followers of the Jesuits.

The Jesuit missionaries were exiled to Canton and then to Macao. Of course a person as talented and helpful as Giuseppe Castiglione in the imperial court, and other missionaries who had technical skills and scientific knowledge were treated as exceptions.

In contrast to the ban on Christianity, Yongzheng tried to lessen the traditional, harsh capital punishments on breaching of official intellectual taboos, instead ordered publication of his writings to debate and indoctrinate on the issues – including on the issue of whether he had “usurped” the throne. But the new approach was abruptly ended with his 13-year rule upon his death, and those not receiving the capital punishment under Yongzheng were given it by his son Qianlong. (See, e.g., The search for modern China, by Jonathan D. Spence, W. W. Norton & Company, 1991; and, “元明清史”, by 王天有 and 成崇德, 五南圖書出版股份有限公司, 2002.)

By the mid-18th century foreign trade with the West was also banned in China except within the Canton System, i.e., at the port of Canton on the Pearl-River Delta near the southern coast. In contrast, Yongzheng and Qianlong gradually relaxed restrictions previously in place on Chinese traders engaging in overseas trade with Southeast Asia. (See, e.g., The Canton trade: life and enterprise on the China coast, 1700-1845, by Paul Arthur Van Dyke, Hong Kong University Press, 2005; and, “Canton System - A Complement to the Old China Trade”, Cultural China; and, China’s Last Empire: The Great Qing, by William T. Rowe, Harvard University Press, 2009.)

Giuseppe Castiglione died in Beijing on July 17, 1766, nearly an exact century from Johann Adam Schall von Bell’s death on August 15, 1666, having born in the same year 1688 when Ferdinand Verbiest died. Several years later the Jesuit society was disbanded by the Catholic Church – coincidentally when the Church had finally lifted its ban on Galileo’s system of astronomy – until the year 1814. “Christianity and the Jesuits in China”, the Royal Academy of Arts, London; and, “Society of Jesus”, Wikipedia.)

A British delegation to Beijing led by Lord Macartney in 1792 failed to lead to more open official trade or official diplomatic relation – with the ineptitude magnified in an anecdote where the official speeches by Macartney had to be first translated from English to Latin for the benefit of the Chinese interpreter who in turn translated them to Chinese for the Qianlong Emperor. (See, e.g., “From the Society of Jesus to the East India Company: A Case Study in the Social History of Translation”, by Sean Golden, in Beyond the Western Tradition. Translation. Perspectives XI, edited by Marilyn Gaddis Rose, Centre for Research in Translation, State University of New York at Binghamton, 2000; and, “Macartney Embassy to China: a diplomatic failure”, by Paulo Roberto Almeida (source: New World Encyclopedia), Shanghai Express (blog), November 13, 2009.)

At the time the British East India Company had a monopoly control of the British official trade with China, and a large part of its actual trade was the illegal trafficking of opium from India – opium sale other than for medicinal purposes having already been banned in 1729 by Yongzheng and trafficking banned in 1735 by Qianlong. (See, e.g., China’s Drug Practices and Policies: Regulating Controlled Substances in a Global Context, by Hong Lu, Terance D. Miethe and Bin Liang, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2009.)

The aspiration to achieve a “Perfect Ming”, if the Qing emperors indeed had that in mind where the Ming dynasty had failed, was going down in a pattern similar to the Ming’s before them. By the time China re-opened again in the mid-19th century, it would literally be forced to do so under the guns of European powers.

|

| The Thirteen Foreign Factories of Canton, circa 1805 (MIT Visualizing Cultures) |

In the early 19th century, the first Protestant missionaries began to arrive in China. They were sent by the London Missionary Society, starting with Rev. Robert Morrison (马礼逊) in 1807 and Rev. William Milne (米怜) in 1813. Affiliated with the British East India Company, the missionaries were very limited in their reach into the local Cantonese, let alone the majority of the Chinese. Distributing the Bible and pamphlets was a main method of preaching, and the printer who did work for Morrison, Liang Fa (梁发), became one of the first Chinese Protestants when he was baptized by Milne in Malacca, where they could conduct Christian printing operation legally. (See, e.g., “List of Protestant Missionaries to the Chinese”, The Chinese repository, Volume 20, by Elijah Coleman Bridgman and Samuel Wells Williams, 1851; “Religion and rebellion in China: the London Missionary Society collection”, by Andrew Gosling, National Library of Australia News, July 1998; “Liang Fa (Ah Fa, Leung Faat, Leong Kung Fa) 1789 ~ 1855”, Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Christianity; and, my first blog posts dated January 29, 2009, “Greeting the New Millennium – nearly a decade late”.)

The German Lutheran missionary Rev. Charles Gutzlaff (郭士立, or 郭实猎, Karl Friedrich August Gutzlaff) was a singular pioneer in the early formation of the Protestant transnational networks from Southeast Asia to China. Sent by the Netherlands Missionary Society, Gutzlaff was the first Protestant missionary to reach Siam (Thailand), arriving in 1828, and is also considered the first non-British Protestant missionary to China – ahead of American missionary Rev. Elijah Bridgman (裨治文). (See, e.g., “The death of the Rev. Charles Gutzlaff at Hong Kong, August 9” and “List of Protestant Missionaries to the Chinese”, The Chinese repository, Volume 20, by Elijah Coleman Bridgman and Samuel Wells Williams, 1851.)

Gutzlaff’s first Chinese convert in Bangkok, Boon Tee, was an immigrant from the Chaozhou region (a prefecture, later also known as Swatow for the port city of Shantou in the region) in eastern Kwangtung (Guangdong) province neighbouring southern Fujian (Fukien) province. (See, e.g., “The Chinese Christian Transnational Networks Of Bangkok-Hong Kong-Chaozhou in the 19th Century”, by Joseph Tse-Hei Lee, Department of History, Pace University, May 2004; and, Opening China: Karl F.A. Gützlaff and Sino-Western relations, 1827-1852, by Jessie Gregory Lutz, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2008.)

The Chaozhou-speaking were the largest group of Chinese in Siam at the time. Their dialect is similar to that in southern Fujian and different from Cantonese spoken in Guangzhou (Canton) where I grew up, and the ancestors of many of them had originally come from Fujian.

Gutzlaff was apparently fluent in the Fujian dialect.

The Chaozhou region’s Christian heritage would include that of my maternal family’s, as I have mentioned earlier my great-great grandfather studied medicine at the Swatow Mission Hospital during the 1860s and became one of the first Chinese doctors of Western medicine in that region. He later also became an ordained Presbyterian minister.

The date of February 19, 2010 for this blog post and for my first Chinese blog post on 高峰的博客 (and its companion blog in China, 高峰的凤凰博客) has been chosen for the reason that in the Chinese Lunar Calendar it happens to be the sixth day of the Chinese year – my maternal grandmother’s birthday. My father’s birthday happens to be on February 20, which I discussed last year in another context in my ongoing, multi-part blog article on Canadian politics.

In the early 1830s at Charles Gutzlaff’s initiation, the American Baptist Missionary Union sent its first missionaries to Thailand and China, Rev. John Taylor Jones in 1832 and Rev. William Dean (憐为仁) in 1835, who set up a base in Bangkok to preach to the local Chinese community – with the objective of expanding into China. (See, e.g., Joseph Tse-Hei Lee, referred to earlier).

Gutzlaff also undertook a number of important journeys along the Chinese coasts and into inland China, on most of them working as an interpreter for opium traders. Gutzlaff’s mastery of various Chinese dialects and customs grew to a point that starting in late 1834 (shortly after the death of Robert Morrison) he became an official Chinese interpreter for the British administration in China. (See, e.g., Journal of three voyages along the coast of China, in 1831, 1832, & 1833: with notices of Siam, Corea, and the Loo-Choo Islands, by Karl Friedrich August Gützlaff and William Ellis, F. Westley and A.H. Davis, 1834; and, “The legacy of Karl Friedrich August Gutzlaff”, by Jessie G. Lutz, International Bulletin Of Missionary Research, Vol.24, No.3, July 2000.)

In Macao in 1835, Gutzlaff met several Japanese persons who on their ship had been blown off course by a typhoon to the Oregon coast, taken slaves by North American natives, and rescued by the Hudson Bay Company and sent from Canada to Macao. With their help Gutzlaff produced the first Japanese translation of a part of the Bible. (See, e.g., Jessie Gregory Lutz, referred to earlier; and, The Bible and Missions, by Helen Barrett Montgomery, BiblioBazaar, LLC, 2009.)

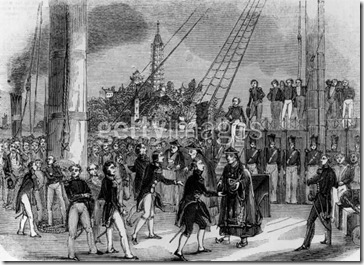

In his official role with the British, Gutzlaff was a key negotiator when the Chinese government brought in an opium ban that was resolutely enforced by Imperial Commissioner Lin Zexu (林则徐, Lin Tse-hsu). The conflict led to an 1839 letter from Commissioner Lin to Queen Victoria to protest the opium trade, and the dispatch of the British navy to China in the Opium War (1839-1842) to protect British commercial interests, which Gutzlaff participated in. That led to the 1842 Treaty of Nanking, signed with the British laying siege to the former Chinese capital at the Yangtze River near the eastern coast; Gutzlaff acted as one of 3 interpreters for the treaty negotiations, and in 1843 became the official Chinese Secretary to the British administration now based in the colony of Hong Kong, upon the island’s cession to Britain as part of the treaty. (See, e.g., “The death of the Rev. Charles Gutzlaff at Hong Kong, August 9”, by Elijah Coleman Bridgman and Samuel Wells Williams, referred to earlier; The Opium War through Chinese eyes, by Arthur Waley, Stanford University Press, 1958; Trade and Diplomacy on the China Coast: The Opening of the Treaty Ports, 1842-1854, by John King Fairbank, Stanford University Press, 1964; “The Treaty of Nanking: Form and the Foreign Office, 1842-43”, by R. Derek Wood, Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, Vol. 24 (2), May 1996; Foreign mud: being an account of the opium imbroglio at Canton in the 1830's and the Anglo-Chinese war that followed, by Maurice Collis, New Directions Publishing, 2002; and, “Lin Zexu (LinTse-hsu) writing to Britain's Queen Victoria to Protest the Opium Trade, 1839”, USC-UCLA Joint East Asian Studies Center.)

During the 1830-40s, Gutzlaff was intimately involved in many private meetings and formal negotiations between the British and the Chinese officials. His indispensability to the British could mean the difference between peace and confrontation in a situation, as seen in an episode during the Opium War when he served as the British-appointed magistrate of Zhoushan (舟山, Chusan), a strategic east-coast island-city the British captured and held for a time, which they really liked (but reluctantly accepted only cession Hong Kong, then a barren island near Canton and Macao in the south) (see, John King Fairbank; referred to earlier):

“When Gutzlaff was transferred from Chusan to take the place of J. R. Morrison as Chinese secretary in the superintendency of trade at Hongkong, the military government of Chusan was left without an interpreter; and when Chinese authorities came to take a register of fishing vessels late in 1843 the British army officers in charge drove them summarily away under the Anglo-Saxon misapprehension that they were trying to hold court and flout the Queen. When translated at Hongkong, their communications were found to be both polite and innocuous.”

The J. R. Morrison referred to in the above quote was the son of Robert Morrison– the first Protestant missionary to China. The junior Morrison was the official Chinese secretary to the British authority – a job he had taken over when his father died in 1834 – and acted as the chief interpreter for the Treaty of Nanking negotiations, but when he soon died in 1843 around the one-year anniversary of the Treaty – at a young age of only 29 – Gutzlaff was given the job. (See, e.g., R. Derek Wood, referred to earlier; and, The China Mission: Embracing a History of the Various Missions of All Denominations among the Chinese, with Biographical Sketches of Deceased Missionaries, by William Dean, Sheldon, 1859.)

Organization was another of Gutzlaff’s strengths, though it would ultimately become his Achille’s Heel. Continuing as a Christian missionary while holding the official Chinese Secretary position in the British colonial government, in 1844 Gutzlaff formed his own Chinese missionary organization, the Chinese Union.

In the next several years Gutzlaff’s organization reached far and wide into the various regions of southern China; of particular interest, in the year 1847 a person of Chaozhou (Swatow) background, “Ming”, became president of this organization. (See, e.g., Joseph Tse-Hei Lee, referred to earlier).

But the authenticity of the Chinese Union members’ Christian belief and Gutzlaff’s own ‘double duties’ were matters of concern among other Western missionaries.

|

| Signing of the Treaty of Nanking aboard HMS Cornwallis, August 29, 1842 (Getty Images) |

It would not be difficult to see why other missionaries hesitated: the Treaty of Nanjing Charles Gutzlaff and J. R. Morrison had taken part in negotiating made no mention of protecting Christian missions, but was preoccupied with reparations for the war and for damages to the British merchants including for the opium destroyed, with future trade privileges at the port of Canton and the additional ports of Amoy (Xiamen) and Foochow (Fuzhou) in Fujian province in the southeast and Ningpo (Ningbo) and Shanghai in the eastern coast, and with cession of Hong Kong to Britain. (See, e.g., “Treaty of Nanjing (Nanking), 1842”, UCLA Asia Institute.)

Following the Opium War, in 1843-45 a number of other Western powers sent their navy ships to the coasts of China, in the hope of obtaining similar legal trade privileges granted Britain by the Qing government. Although the primary objectives in the showing of military might and in the subsequent treaty negotiations were commercial, both the United State and France asked for and received treaty concessions for limited rights and protection of foreign missionaries.

With a small naval fleet, the U.S. negotiated and won the 1844 Treaty of Wangxia (Wanghia, 望厦条约), receiving permission for American missionaries to preach Christianity and establish churches in the five open ports. The Americans also won extraterritoriality for their citizens in China, i.e., any American accused of a crime would be handled by the American consul under the U.S. law, but with an explicit exception on anyone caught smuggling opium or contraband goods. (See, e.g., Modern China: An Encyclopedia of History, Culture, and Nationalism, by Ke-wen Wang, Taylor & Francis, 1998; Westerners in China: A History of Exploration and Trade, Ancient Times through the Present, by Foster Stockwell, McFarland, 2003; and, “The Opening to China Part I: the First Opium War, the United States, and the Treaty of Wangxia, 1839-1844”, U.S. Department of State.)

Closely following, in the 1844 Treaty of Whampoa (黄埔条约) France won privileges similar to what the Americans received, including the rights to preach Christianity and establish churches in the five open ports.

But with the backing of a large naval fleet, the French Ambassador Theodore de Lagrene, who was also a high-ranking Jesuit, decided to also demand Chinese imperial lifting of the ban on Christianity, which had been in place since the Yongzheng Emperor’s 1724 edict. After many months of bargaining and pressures by the French, the Daoguang Emperor (道光) issued a number of edicts in 1844-46, making Christianity legal in China and ordering the return of church properties confiscated over a century ago. (See, e.g., China: Political, Commercial, and Social; In an Official Report to Her Majesty’s Government, Volume 2, by R. Montgomery Martin, J. Madden, 1847; France Overseas: A Study of Modern Imperialism, by Herbert Ingram Priestley, Routledge, 1967; and, Ke-wen Wang, referred to earlier.)

In an 1847 official report to the British government in London, Robert Montgomery Martin, the treasurer for the British colonial government and diplomatic services in China, lamented about Britain’s focus on opium trade and not on Christianity (see, R. Montgomery Martin, referred to earlier):

“Our Government appear ashamed of Christianity as if its principles were poison and its professors demons. At the treaty of Nankin we made less mention of our religion than any heathens would have done; we did not require permission to erect a place of worship at the consular ports, or even to form a Christian burial-ground; thanks to the French and Americans, these two points since been obtained. We do not appear to have given ourselves the least trouble on the subject; it is as well we did not: we were far more solicitous about licensing opium smoking at Hong Kong, than of building even a Protestant church there. Even the circular to our consuls in China, from Her Majesty’s government in England, was hostile to English missionaries at the consular ports!”

Though Christianity was now legal in China, foreign missionaries were still restricted from freely venturing into China outside of the five open ports.

(To be continued in Part 2)